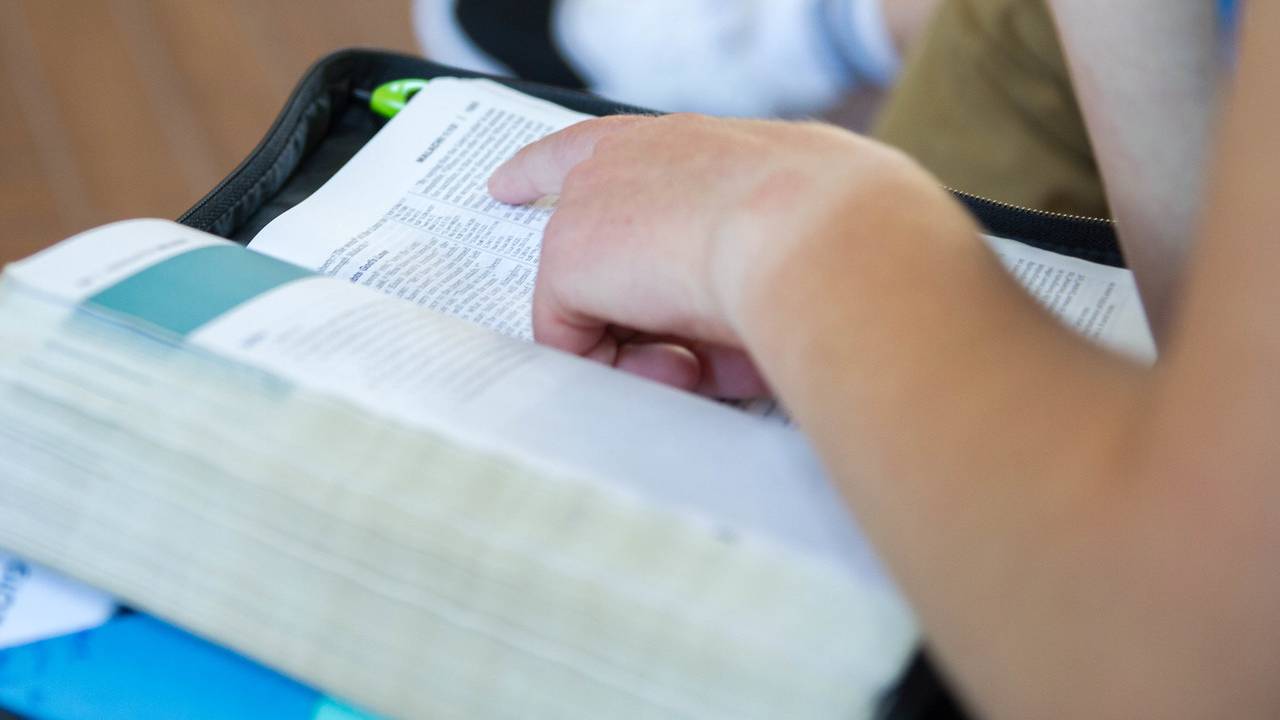

What does the Bible say about race?

June 23, 2020

- J. Danny Hays

June 23, 2020

- J. Danny HaysCreated in the image of God

Any serious biblical study of race or ethnicity should start in Genesis 1. The Bible does not start off with the creation of a special or privileged race of people. When the first human being is created he is simply called adam, which is Hebrew for “humankind.” Adam and Eve are not Hebrews or Egyptians; they are neither White nor Black nor even Semitic. Their own particular ethnicity is not even mentioned, for the Bible seems to stress that they are the mother and father of all peoples of all ethnicities. Adam and Eve are presented as non-ethnic and non-national because they represent all people of all ethnicities.

In Genesis 1:26 God says, “Let Us make man (adam) in Our image, according to Our likeness.” Then 1:27 describes his creative action: “So God created man (adam) in His own image; He created him in the image of God; He created them male and female.”[1] The “image of God” relates to one or more of the following: 1) the mental and spiritual faculties that people share with God; 2) the appointment of humankind as God’s representatives on earth; and 3) a capacity to relate to God. Yet what is clear is that being created in “the image of God” is a spectacular blessing; it is what distinguishes people from animals. Likewise, whether or not the “image of God” in people was marred or blurred in the “Fall” of Genesis 3, it is clear that at the very least people still carry some aspect of the image of God, and this gives humankind a very special status in the creation. Furthermore, as mentioned above, Adam and Eve are ethnically generic, representing all ethnicities. Thus the Bible is very clear in declaring from the beginning that all people of all races and ethnicities carry the image of God.

This reality provides a strong starting point for our discussion of what the Bible says about race. Indeed, John Stott declares, “Both the dignity and the equality of human beings are traced in Scripture to our creation.”[2] To presuppose that one’s own race or ethnicity is superior to someone else’s is a denial of the fact that all people are created in the image of God.

The Book of Proverbs presents several practical implications from this connection between God and the people he created. For example, Proverbs 14:31a states, “The one who oppresses the poor insults their Maker.” Proverbs 17:5a echoes this teaching, “The one who mocks the poor insults his Maker.” These verses teach that those who take a superior attitude toward others due to their socio-economic position and thus oppress or mock others are in fact insulting God himself. To insult or mistreat the people God has created is an affront to him, their Creator. The same principle applies to racial prejudice. The unjustified self-establishment of superiority by one group that leads to the oppression of other groups is an affront to God. Likewise, the mocking of people God created—and this would apply directly to ethnic belittling or “racial jokes”—is a direct insult to God. All people of all ethnicities are created in the image of God. Viewing them as such and therefore treating them with dignity and respect is not just a suggestion or “good manners,” it is one of the mandates emerging out of Genesis 1 and Proverbs.

The so-called “Curse of Ham” (Genesis 9:18-27)

In regard to the history of racial prejudice in America no other passage in Scripture has been as abused, distorted and twisted as has Genesis 9:18-27. Thus it is important that we clarify what this passage actually says (and doesn’t say).

In Genesis 9:20-21, after the flood is over and his family has settled down, Noah gets drunk and passes out, lying naked in his tent. His son Ham, specifically identified as the father of Canaan (9:22), sees him and tells his two brothers Shem and Japheth, who then carefully cover up their father. When Noah wakes up and finds out what happened he pronounces a curse on Canaan, the son of Ham, stating, “Cursed be Canaan! The lowest of slaves will he be to his brothers.” Noah then blesses Shem and Japheth, declaring, “Blessed be the LORD of Shem! May Canaan be the slave of Shem. May God extend the territory of Japheth. . . and may Canaan be his slave” (9:26-27).

In the 19th century, both before and after the Civil War, this text was frequently cited by Whites to argue that the slavery or subjugation of the black races was, in fact, a fulfillment of the prophecy in this text. These pastors and writers argued that 1) the word “Ham” really means “black” or “burnt,” and thus refers to the Black race; and 2) God commanded that the descendants of Ham (Black people) become slaves to Japheth, who, they argued, represents the White races.[3]

It should be stated clearly and unambiguously that every reputable evangelical Old Testament scholar that I know of views this understanding of Genesis 9:18-27 as ridiculous, even ludicrous. It is completely indefensible on biblical grounds.

First of all, note that the curse is placed on Canaan and not on Ham (Gen. 9:25). To project the curse to all of Ham’s descendants is to misread the passage. It is Canaan (and the Canaanites) who are the focus of this curse. This text is a prophetic curse on Israel’s future enemy and nemesis, the Canaanites. The Canaanites are included here in this prophetic curse because they are characterized by similar sexual-related sins elsewhere in the Pentateuch (see Lev. 18:2-23 for example). The curse on Canaan is not pronounced because Canaan is going to be punished for Ham’s sin, but because the descendants of Canaan (the Canaanites) will be like Ham in their sin and sexual misconduct.

Furthermore, it is wildly speculative to assume that the name Ham actually means “black” and thus refers to the people in Black Africa. There is an ancient Egyptian word keme that means “the black land,” a reference to the land of Egypt and to the dark fertile soil associated with Egypt. Yet to assume that the Hebrew name Ham is even connected at all to this Egyptian word is questionable. Then even if it is, to say that “the black land,” a reference to fertile soil, is actually a reference to Black races in Africa is likewise quite a leap in logic. Thus the etymological argument that “Ham” refers to the Black peoples of Africa is not defensible. Likewise, as mentioned above, the actual curse is on Canaan, who is clearly identified as the son of Ham. Thus the curse is placed on the Canaanites and not on the supposed (and unlikely) descendants of Ham in Black Africa.

This passage finds fulfillment later in Israel’s history during the conquest of the Promised Land when the Israelites defeat and subjugate the Canaanites. It has absolutely nothing to do with Black Africa or the subjugation of Black peoples. Such an interpretation seriously distorts and twists the meaning of this passage.

The ethnic composition of biblical Israel

Using cultural and geographical “boundary markers” such as language, territory, religion, dress, appearance, and ancestor origins, the ancient peoples in the regions in and around ancient Israel can be split up into four major ethnic groups: 1) the Asiatics or Semites (including the Israelites, Canaanites, Amorites, Arameans, etc.); 2) the Cushites (Black Africans living along the Nile River south of Egypt; also referred to as Nubians or Ethiopians, although they are not connected to modern Ethiopia); 3) the Egyptians (a mix of Asiatic, north African, and African elements), and 4) Indo-Europeans (Hittites, Philistines).

Ancient Israel develops from within the Asiatic/Semitic group of peoples, although several of the other groups have significant input. Note that Israel is not mentioned in Genesis 10 as one of the ancient peoples. When God first calls Abraham, he is living in Ur of the Chaldees, an Amorite region of Mesopotamia. Yet later in the Bible, Abraham is most closely associated with the Arameans (Gen. 24:4; 28:5; Deut. 26:5). While both Abraham’s son Isaac and grandson Jacob marry Aramean women, the next generation also marries Canaanites (Judah, Gen. 38:2; Simeon, Gen. 46:10) and Egyptians (Joseph, Gen. 41:50).

Thus at the dawning of the Israelite nation, the descendants of Abraham are a mix of Western Mesopotamian (Aramean and/or Amorite), Canaanite, and Egyptian elements, and looked very much like the Semitic peoples of the Middle East today, such as modern Arabs and Israelis.

It is during the 400 plus year sojourn in Egypt that the family of Abraham develops linguistically and culturally into an identifiable Israelite people. Yet even then, in terms of ethnicity they are hardly monolithic. In addition to the various ethnic streams that influence the formation of the Israelite nation during the patriarchal period, numerous other ethnic influences continued to shape the formation of Israel. For example, when God delivers Israel from Egypt, the Bible mentions that “an ethnically diverse crowd went up with them” (Exod. 12:38). This term indicates that the group Moses leads out of Egypt and into covenant relationship with God is an ethnically diverse group. The majority of them are probably descendants of Abraham but many of them are not.

At this particular time in Egypt’s history, there are numerous Cushites (Black Africans) living in Egypt, at all levels of society. In all likelihood some of these Africans are part of the “ethnically diverse crowd” that comes out of Egypt and joins Israel. During the exodus Moses will marry one of these Cushites (see below). Likewise, the name of Moses’ great nephew Phinehas, a very prominent priest, suggests a connection with the Cushites. Phinehas’ name is an Egyptian name. The Egyptians referred to the Black African inhabitants of Cush by the ethnic term nehsiu. In Egyptian the prefix “ph” functions like a definite article, so the name “Phinehas” literally means “the Cushite” or “the African,” that is, one of the Black Africans living in Cush.

Moses and inter-ethnic marriage

In the books of Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy the central character, apart from God, is Moses. Appointed by God as Israel’s leader and mediator between God and the people, Moses dominates the human side of the story. Interestingly, the biblical story includes quite a bit of personal information about Moses, even specifically mentioning his two inter-ethnic marriages. Keep in mind that at this time in Israel’s history the norm of monogamous marriage had not yet been established. Recall that even later in history King David will have seven wives, apparently with God’s approval.

Early in Moses’ life he flees from Egypt to Midian, where he meets and marries Zipporah, a Midian woman (Exodus 2). The Midianites are a Semitic-speaking people, ethnic cousins to the Israelites. What is surprising about this marriage is that the Midianites worship Baal. In fact, Reuel, Zipporah’s father, is a priest of Midian (Exod. 2:15-22; Num. 25). At this stage of his life Moses is not serving God yet, and there is no indication that God approves of this marriage. Indeed, later in Numbers 25 the Midianites will appear as a deadly and dangerous theological enemy of Israel who threaten to undermine the theological and ethical faithfulness of Israel to God.

Later in his life, however, while Moses is faithfully leading Israel and serving God, he marries a Cushite woman (Num. 12:1). In the past, some scholars, perhaps bothered by Moses’ marriage to a Black African woman, tried to argue that this woman is actually Zipporah the Midianite. Such an argument is quite weak, however. The Cushites are well-known in the OT and there is nothing ambiguous about their identity or their ethnicity. Moses marries a Black African woman; there is no doubt about this.[4]

Yet what of the biblical injunctions against inter-ethnic marriage? Is Moses violating these commandments? Not at all. In the Pentateuch the prohibition against inter-marrying with other groups always specifically refers to the pagan inhabitants of Canaan (Deut. 7:1-4). The reason for this prohibition is theological. If they intermarry with these pagan peoples, God warns, “they will turn your sons away from me to worship other gods” (Deut. 7:4; see also Exod. 34:15-16). Underscoring this distinction is Deuteronomy 21:10-14, which describes the procedure for how the Israelites are to marry foreign women, a practice that was allowed if the women are from cities that are outside that land; that is, not Canaanite. Later in Israel’s history, Ezra and Nehemiah will reissue the prohibition against intermarriage (Ezra 9:1; Neh. 13:23-27), but once again the context is that of marrying outside the faith. Both Ezra and Nehemiah seem to stress that earlier intermarriages (especially Solomon’s) played a negative role in Israel’s apostasy and idolatry.

The implications of Moses’ marriage to a Cushite woman are significant. Moses is one of the leading figures in the OT. As the story unfolds in Numbers 12:1-16 it is clear that God approves of this marriage, for he rebukes Miriam and Aaron for opposing it, and he then strongly reaffirms Moses as his chosen leader. Thus early in Israel’s story we find one of Israel’s most faithful leaders intermarrying with a Black African woman while serving God faithfully.

The conclusion we can draw from these Scripture passages is that interracial marriage is strongly affirmed by Scripture, if the marriage is within the faith. Marriage outside of the faith, however, is prohibited.

The Cushite Ebed-Melech: Hero and representative of gentile inclusion

Ebed-Melech the Cushite plays a key role in the Book of Jeremiah, both historically and theologically. Jeremiah the prophet preaches for years against the sinful actions of the leaders and the people in Judah, but meets only with rejection and hostility. As Jeremiah has predicted, the Babylonian army invades and lays siege to Jerusalem (Jeremiah 38-39). The leaders in Jerusalem, rather than listening to Jeremiah, instead accuse him of treason, and lower him down into a muddy water cistern, ostensibly to let him die there. At this point in the story, no one in Jerusalem believes the word of God spoken by Jeremiah or stands up for him. His message is ignored and he is left to die in the cistern as the Babylonian siege rages.

An unlikely hero emerges at this point. A man named Ebed-Melech, identified repeatedly as a Cushite (i.e. a Black African from the region along the Nile south of Egypt), confronts King Zedekiah and obtains permission to rescue Jeremiah from the cistern, probably saving the prophet’s life. Soon Jerusalem falls to the Babylonians, who then execute most of the leaders who had opposed and persecuted Jeremiah. At this point God makes a clear statement about the fact that Ebed-Melech will live and be delivered because of his trust in God (Jer. 39:15-18).

In essence God does for Ebed-Melech precisely what he would not do for King Zedekiah and the other leaders of Jerusalem—save him from the Babylonians. The contrast is stark, and in this context Ebed-Melech plays an important theological role in the story. At a time when all of Jerusalem has rejected the word of God—thus falling under his judgment—this Cushite foreigner trusts in God and finds deliverance. Ebed-Melech, a Black African, stands as a representative for those Gentiles who will be incorporated into the people of God by faith.

There is a tendency among White Christians to view the biblical story as primarily a story about them (White people), with people of other ethnicities either absent from the story or added on peripherally later in the story. In reality, the story of Israel is a multi-ethnic story. The ancient Hebrews are a mix of ethnicities, with continual influxes of other nationalities. At the center of this trend is Moses’ marriage to a Cushite woman. Likewise, at a very critical juncture in the story, it is the Cushite Ebed-Melech who emerges as the example and representative of the future inclusion of Gentiles who will be added to the people of God based on faith.

The Gospels and Acts: Crossing ethnic lines with the Gospel

One of the central themes introduced in the Gospels and brought to the forefront of the story in Acts is that the gospel is for all peoples and ethnicities. There are numerous allusions in the Gospels to the Abrahamic promise in Genesis regarding the blessings that will come through Abraham and his descendants to peoples and nations (Gen. 12:3; 22:18). Likewise the Gospel of Matthew closes with the Lord’s command to “go and make disciples of all nations” (Matt. 28:19). Also significant is the observation that Matthew 1 includes several inter-ethnic marriages in the genealogy of Jesus. Tamar and Ruth were Canaanites, while Ruth was a Moabitess. The ethnicity of Bathsheba is not known, but she was married to a Hittite named Uriah, so possibly she was also a Hittite. The point of mentioning these foreign women in the genealogy of Jesus is to highlight the mixed nature of Jesus’ lineage, suggesting and alluding to the upcoming Gentile mission and speaking to the readers of their responsibility to cross cultural and ethnic boundaries to spread the gospel.[5]

Luke and Acts in particular are especially concerned with developing this theme of Gentile inclusion and the crossing (or obliterating) of cultural or ethnic boundaries between peoples with the gospel. In the parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25-37), for example, Jesus teaches that loving your neighbor as yourself means loving those in particular who are different than you ethnically. That is his point in using the ethnically explosive Judean-Samaritan situation for the background of his parable. At this time the Judeans and Samaritans hate each other and ethnic tensions between them are high. Yet Jesus tells the story to a Judean audience with the Samaritan as the hero, clearly teaching his audience that “loving one’s neighbor” meant crossing ethnic lines and caring for those who were ethnically different. Jesus also explicitly mentions crossing this same ethnic and cultural boundary in his marching orders to his disciples in Acts 1:8, “you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem, in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth.”

Continuing with this theme, as the Jewish leaders in Jerusalem reject the message of Christ and begin openly persecuting the apostles, Acts 8 presents the story of how an Ethiopian believes in the gospel and is saved. The term translated as “Ethiopia” in the NT refers to the exact same region that “Cush” refers to in the OT. Similar to Ebed-Melech the Cushite in Jeremiah 38-39, this Ethiopian in Acts 8 believes the word of God proclaimed by the prophets and trusts in God, thus finding salvation, in contrast to the leaders back in Jerusalem. As the first Gentile believer in Acts, this Ethiopian serves as the fore-runner or model representative of the coming Gentile inclusion, much like the role of Ebed-Melech in Jeremiah.

Paul and Revelation: Building the unified, multi-ethnic church

At the center of Paul’s theology is the doctrine of justification by faith. That is, believers are forgiven their sins and are justified before God by the grace of God through faith in Christ. Yet Paul also develops the consequential and practical outworking of this doctrine. Since we all come before God based on what Christ has done for us rather than what we have done, then we are all equal before him. Paul stresses this in passages such as Galatians 3:28, “There is no Jew or Greek, slave or free, male or female; you are all one in Christ Jesus.” The slightest notion of ethnic superiority is a denial of the theological reality of justification.

Furthermore, Paul’s emphasis is not just on equality, but on unity. Thus in Colossians 3:11 he writes, “Here there is not Greek and Jew, circumcision and uncircumcision, barbarian, Scythian, slave and free; but Christ is all and in all.” Likewise in Ephesians 2:14-16 Paul stresses that in Christ groups that were formerly hostile (like the Jews and Gentiles) are now brought together in unity in one body.

Paul is not just commending toleration of other ethnic groups in the Church, he is teaching complete unity and common identity among the groups. He proclaims that we are all members of the same family, parts of the same body. Once we have been saved by faith and brought into Christ, then our perception of our self-identity must change, leading to a radical shift in thinking about other groups of people within the faith as well. Our primary identity now lies in the fact that we are Christians, part of Christ and his kingdom. This overshadows and overrides all other identities. Thus the primary identity for us, whether we are White Christians or Black Christians (or Asian or Latin American, etc.) is that we are Christian (“in Christ”). This should dominate our thinking and our self-identity. We should now view ourselves as more closely related to Christians from other ethnicities than we are to non-Christians of our own ethnicity. We don’t just tolerate each other or “accept” each other; we realize that we are connected together into one entity as kinfolk, brothers and sisters of the same family, united and on equal footing before God, and only because of what God has done for us. This does not obliterate the reality of skin color or cultural differences. What it changes is where we look for our primary self-identity. Our ethnic distinctions should shrink to insignificance in light of our new identity of being “in Christ” and part of his family.

This unity is brought to a climax in the Book of Revelation. Central to the climactic consummation presented in Revelation is the gathering of multi-ethnic groups around the throne of Christ. Revelation 5:9 introduces this theme by proclaiming that Christ has redeemed people “from every tribe and language and people and nation.” This fourfold grouping (tribe, language, people, nation) occurs seven times in Revelation (5:9; 7:9; 10:11; 11:9; 13:7; 14:6; 17:15). In the symbolic world within the Book of Revelation the number four represents the world while the number seven represents completion. Thus the seven-fold use of this four element phrase is an emphatic indication that all peoples and ethnicities are included in the final gathering of God’s redeemed people around his throne to sing his praises. [6]

Conclusions

The main points of this study [7] can be synthesized into the following points:

- The biblical world was multi-ethnic, and numerous different ethnic groups, including Black Africans, were involved in God’s unfolding plan of redemption.

- All people are created in the image of God, and therefore all races and ethnic groups have the same equal status and equal unique value.

- Inter-ethnic marriages are sanctioned by Scripture when they are within the faith.

- The gospel demands that we carry compassion and the message of Christ across ethnic lines.

- The NT teaches that as Christians we are all unified together “in Christ,” regardless of our differing ethnicities. Furthermore, our primary concept of self-identity should not be our ethnicity, but our membership as part of the body and family of Christ.

- The picture of God’s people at the climax of history depicts a multi-ethnic congregation from every tribe, language, people, and nation, all gathered together in worship around God’s throne.

By Dr. J. Daniel Hays, professor emeritus of biblical studies. This article appears and is adapted from The Gospel & Racial Reconciliation (Gospel for Life Series) edited by Russell Moore and Andrew T. Walker, B&H, 2016.

[1] Biblical citations will be from the Holman Christian Standard Bible.

[2] John R. W. Stott, Human Rights and Human Wrongs: Major Issues for a New Century (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 1999), 174-75.

[3] For a more detailed discussion, see J. Daniel Hays, From Every People and Nation: A Biblical Theology of Race, NSBT (Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 2003), 52-54.

[4] See the discussion on this marriage in Hays, From Every People and Nation, 70-77.

[5] Craig S. Keener, A Commentary on the Gospel of Matthew (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1999), 79-80. See also Hays, From Every People and Nation, 158-60.

[6] Richard Bauckham, The Climax of Prophecy: Studies in the Book of Revelation (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1993), 336. See also the discussion in Hays, From Every People and Nation, 193-200.

[7] From Hays, From Every People and Nation, 201-206.

You Also Might Like

Recent